Haifisch in Vogeltränke

2003-2004

Oil on Canvas

Der Haifisch in der Vogeltränke

Man stelle sich vor, ein Familienfotoalbum würde Aufnahmen enthalten, die das Sterben des Großvaters, den Ehestreit der Eltern, die im Schwimmbecken ertrunkene Katze, die weinende Mutter, den Hautauschlag der Tochter, den prügelnden Vater und ähnliche Motive zeigen – unvorstellbar, da es einem kulturellen Tabu gleichkäme. Als abbildungs- und erinnerungswürdig gelten fast ausschließlich positiv assoziierte Situationen wie die Geburtstagsparty, die Urlaubsreise, der Sonntagsausflug, die Abiturfeier, die Hochzeit, das eigene Haus und der blühende Garten, das lachende Baby und Ähnliches. Wie Rosalind E. Krauss hervorhebt, hat die Fotokamera »ihren Platz innerhalb des ritualisierten Kults häuslichen Lebens und wird auf die Momente getrimmt, die innerhalb dieses Kults heilig sind«. Das ideologische Konstrukt des Fotoalbums impliziert, dass alle Konflikte und Schattenseiten des Lebens im Bild grundsätzlich ausgeblendet bleiben.

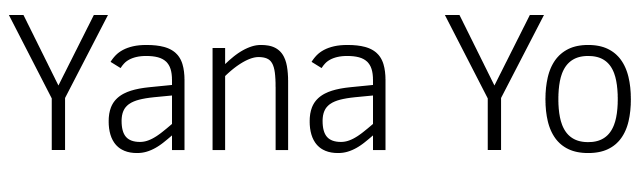

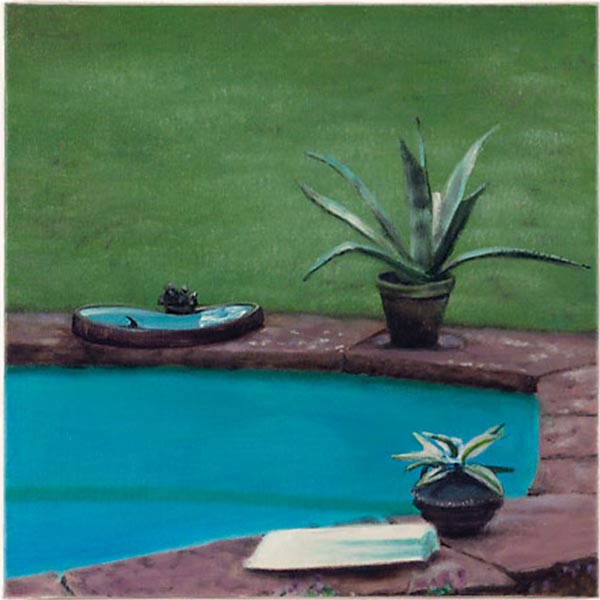

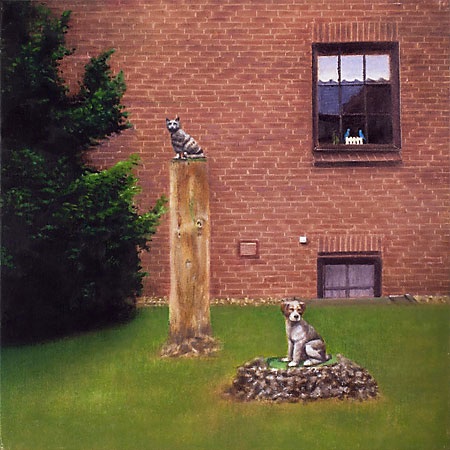

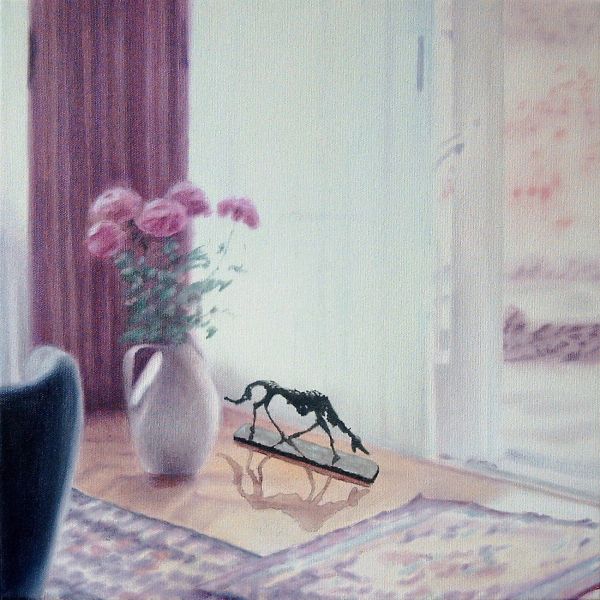

Auf den ersten Blick könnte man vermuten, dass auch Yana Yos weitgehend realistische Gemälde traditionelle Vorstellungen vom häuslichen Glück und von der harmonischen Lebenswelt der Familie vermitteln und bestätigen wollen. 2003 produzierte die Künstlerin 15 kleinformatige Ölbilder (40 x 40 cm), die alle auf Fotografien aus den fünfziger und sechziger Jahren basieren. Die Aufnahmen, die sich auf einem Flohmarkt fanden, wurden von einem unbekannten Knipserfotografen offensichtlich zum rein privaten Gebrauch und ohne künstlerische Ambitionen angefertigt. Diese fotografischen Vorlagen zeigen unter anderem Gartenstühle auf einer Terrasse, einen Swimmingpool mit Vogeltränke und Topfpflanzen, kitschige Tierplastiken in einem Vorgarten, ein Wohnzimmer mit Sitzgruppe und Fensterbank, eine kleine Vase mit Blumen, den Blick durch ein Fenster auf eine unbekleidete Person im Garten, ein Handtuch auf einer Wäscheleine und einen verwackelten Schnappschuss von einer Stadtrundfahrt. Jene beschauliche, kleine, heile Welt und deren spezifische triviale Ästhetik wurden von Yana Yo im Kunstkontext bildwürdig gemacht. Doch die memorierende Funktion der privaten Fotografien verliert in der Malerei gerade durch die Nobilitierung des Trivialen ihre Selbstverständlichkeit, und die Motive werden zu anschaulichen Objekten der Reflektion.

Die Gemälde scheinen für Yana Yo weder das Spiegelbild eigener Wunschvorstellungen noch Abgrenzungsbemühungen gegenüber ihrem Elternhaus zu sein, sondern eher eine analytische Auseinandersetzung mit den Vorstellungen deutscher Wohnästhetik und Gemütlichkeit sowie mit dem darin zum Ausdruck kommenden Ideal einer bürgerlichen Ordnung. So zeigt etwa das Bild Wohnzimmer im Vordergrund ein Sofa mit Kissen, zwei Sesseln und einem Couchtisch, dahinter eine Fensterbank mit einer arrangierten, kleinteiligen Reihe an Blumentöpfen und Vasen, während im Hintergrund ein großes Fenster den Blick freigibt in einen sonnigen Garten. Das Bild vermittelt fast perfekt das Stereotyp des biederen Wohnzimmers der frühen sechziger Jahre mit all seinen Konnotationen von Hausfrauentugenden und demonstrativer Anständigkeit im deutschen Wirtschaftswunder der Adenauer-Ära. Aus jedem Detail dieser Raumansicht artikuliert sich der Wunsch nach bürgerlich-repräsentativer Respektabilität und harmonisch-familiärer Intimität. Die der Generation von Yana Yo noch gut vertraute Ästhetik solcher Räume, deren kulturelle Normierung und die damit implizierten geschlechtsspezifischen Verhaltensweisen ihrer BewohnerInnen werden in den Gemälden bildnerisch reflektiert. Als Teil einer nicht bekannten privaten Biografie sind die Motive gleichzeitig Teil eines kollektiven Bewusstseins, da dieses Ideal bürgerlich-häuslichen Glücks durchaus noch vielen BetrachterInnen vertraut ist.

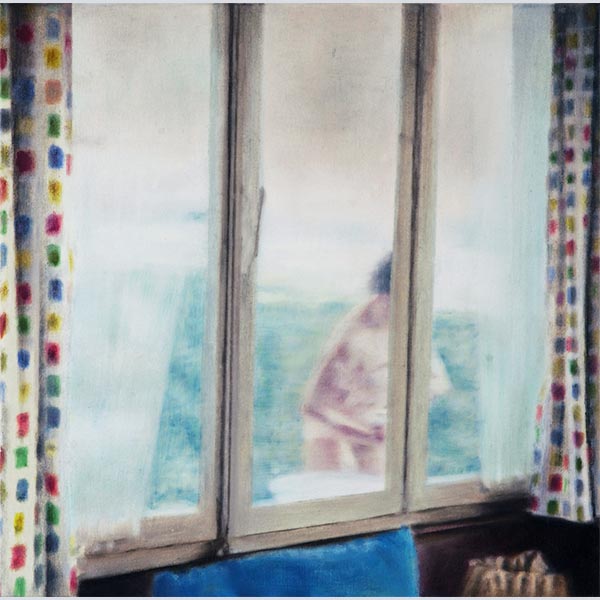

Auch wenn die Künstlerin die fotografischen Vorlagen in ihrer malerischen Transformation teilweise manipuliert hat, indem sie etwa nur einen Ausschnitt übernommen oder die Komposition minimal verändert hat, enthält sie sich jedes eindeutigen Kommentars; sie bleibt also als bedeutungsstiftendes Subjekt im Hintergrund. Die Bilder weisen weder eine ausdrücklich affirmative Sentimentalität auf noch eine explizite Ironie oder gar Zynismus. Es lässt sich jedoch bei einigen Bildern eine verhaltene Ironie und eine gewisse Skurrilität im Detail beobachten,fischem Anspruch auf ein erotisches Motiv und dem missglückten Resultat wirken kurios. Auch das Bild Vorgarten, das einen Hund und eine Katze als Tierplastiken in einem penibel gepflegten Garten darstellt, lebt von dem befremdlichen oder gar witzigen Gegensatz zwischen den höchst naturalistischen Figuren und deren Präsentation auf einem viel zu großen Holzsockel und auf einem lächerlich artifiziellen Podest.

Das mit Haifisch betitelte Gemälde zeigt hingegen den mit Steinplatten belegten Rand eines Swimmingspools und eine sorgfältig in Form gebrachte Rasenfläche; auf dem Beckenrand stehen zwei eingetopfte, südländische Grünpflanzen und eine nierenförmige Vogeltränke. Erst auf den zweiten Blick entdeckt man eine winzige, dunkle Haifischflosse, die aus der Tränke hervorschaut. Die paradiesische Sommerfrische wird auf ironische Weise gebrochen, indem ein Zeichen des Grauens in niedlich miniaturisierter Form aufblitzt. Roland Barthes hat solche Bilddetails in seinem Buch La chambre claire, Note sur la photographie als »punctum« bezeichnet:

»Das punctum einer Photographie, das ist jenes Zufällige an ihr, das mich besticht.« Dabei betont Barthes: »Das Detail, das mich interessiert, ist nicht oder wenigstens nicht unbedingt beabsichtigt [...]; es befindet sich im Umfeld des photographierten Gegenstandes als zugleich unvermeidliche und reizvolle Zutat.« Bei dem Gemälde ist der Haifisch das bildnerische Element, das uns besticht, berührt und irritiert, das die Harmonie zum Kippen bringt, obwohl dies von dem Fotografen sicherlich nicht intendiert gewesen ist. Yana Yo unternimmt in ihren Bildern eine Gradwanderung zwischen Idylle und Skurrilität, dargestellter Biederkeit und Ironie, um dem bürgerlichen Versprechen häuslichen Glücks nachzuspüren, es scheinbar zu bestätigen und gleichzeitig zu entlarven in seiner Fragwürdigkeit.

The Shark in the Bird-Bath

Just imagine, a family photo album containing depictions of the dying Grandfather, parents fighting, the cat drowned in the swimming pool, the weeping Mother, the daughter's rash, Father's fisticuffs and similar motifs - unthinkable. That would equal breaking a cultural taboo. So, worthy of capturing and keeping are almost only those events of positive association; birthday parties, holiday trips, a Sunday outing, the passing out ceremony, a wedding, the house with the garden in full bloom, the baby laughing and other similar snapshots. As Rosalind E. Kraus points out, the camera has its place within the culture of the rituals of family life and is trimmed to capture these moments that are so respected within this framework. The idealistic structure of the family album implies that conflict and the darker side of life simply do not exist.

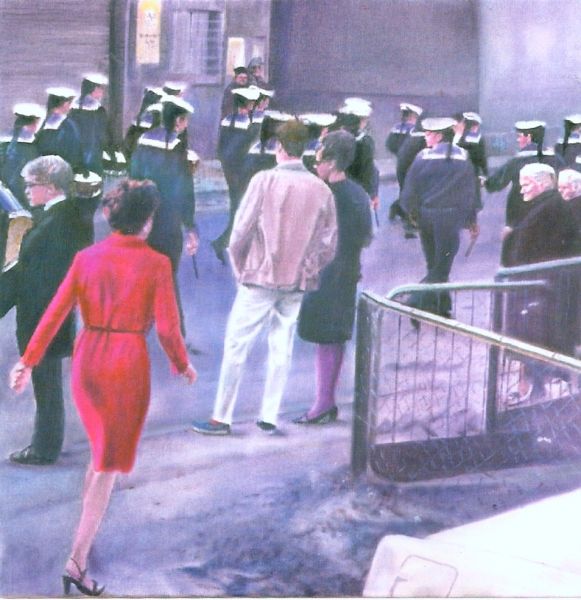

At first sight, one could assume that Yana Yo's rather realistic paintings seek to convey and confirm traditional ideas of the happy family and of the harmonious environment in which it exists. In 2003 the artist produced 15 oils in the small format of 40 x 40 cm., all based on photos taken in the fifties and sixties. These photos, found at a flea market, shot by an unknown amateur and obviously intended for exclusively private use, show no artistic intent at all. The pictorial models show among other things, garden chairs on the patio, a swimming pool with a bird-bath and potted plants, kitsch animal ornaments in a front garden, a living room complete with sitting room furniture and window sill, a small vase with flowers, a glimpse through the curtains showing a person with no clothes on in the garden, a hand-towel on the washing-line and an unsteady shot from a al aesthetic has been given an artistic context of pictorial value. And so in the medium of painting the reminiscence function of these private photographs as well as their independence is lost through her raising the esteem of such trivia so allowing them to become worthy objects of reflection.

For Yana Yo the paintings appear as neither the mirror image of her own personal expectations nor as the striven separation from her parents, but rather an analytical discussion of the conceptions of the aesthetics of life and its "Gemuetlichkeit" (cosiness), having the result that the ideals of the establishment come into the equation. Thus, for instance, the picture "Wohnzimmer" shows a sofa with cushions in the foreground, two chairs and a coffee table, behind that an arrangement on a window sill, a row of knick-knacks, flower pots and vases, while in the background a large window allows a view into a sunny garden. The picture reflects almost perfectly the stereotyped conventional living room of the early sixties together with all the connotations of the virtues of the housewife and the demonstrative decency in that German "Wirtschaftswunder" and the Adenauer era. The desire for representative bourgeois respectability and harmonious-family intimateness a rticulate themselves from every detail of this view of the room. It is Yana Yo's generation that is so familiar with the aesthetic appreciation of such rooms. Cultural standardisation and the so implied gender specific behaviour of the occupants thereby become pictorially reflected in the paintings. Whilst being part of an unknown private biography the subjects are at the same time part of a collective consciousness, this ideal of a happy home still being quite familiar to so many of the works' viewers.

Though the artist did partly manipulate the photographic originals in the pictorial transformation by using only a cropped image or by changing the composition minimally, she withholds any clear comment; she remains in the background thus the donator of meaning to this subject. The pictures point neither to an expressly affirmative sentimentality nor to any explicit irony or even cynicism. However a restrained irony and a certain scurrility in the detail can be observed in some pictures, of which Yana Yo is quite aware and who finds them important. The painting "Voyeur" shows the abashed view through a three-part window framed by coloured curtains, leading out to a naked woman in a summer garden, whereby the figure is partly hidden by the window frame. It is not only this unusual reversal of the voyeur's view from inside into an outside space that comes over funny, but also the discrepancy between the photographic requirements of an erotic motive and the failed result. The picture "Vorgarten", which represents a dog and a cat as animal ornaments in a fastidiously maintained garden also lives from the disconcerting or unusual contrast between the most natural figures and their presentation on a much too large wooden base and on a ridiculously artificial plinth.

The painting with the title "Haifisch" in contrast shows a swimming pool with flags carefully paving the edges of an immaculately kept lawn, on the edge two potted succulents and a kidney shaped bird-bath. Only at second sight does one discover a tiny, dark shark-fin, which pops up from the bird-bath. The paradise-like summer breeze is ironically destroyed, in that this harbinger of horror, in a nicely miniaturised form raises its head. In his book "La chambre claire, note sur la photography." Roland Barthes called such pictorial details 'punctum': "It is the 'punctum' of a photograph, the randomness of it that appeals to me.” Here Barthes stresses; "The detail which interests me is not, or at least not necessarily intentional, (...); it finds itself in the surrounding composition at the same time being the inevitable and the titillating ingredient." In this painting it is the shark that is the pictured element in the surroundings of the photographed subject which captivates, touches and irritates us, which causes the balance of harmony to tilt, although this was surely not what the photographer intended. In her pictures, Yana Yo undertakes a tight-rope walk between the idyllic and the scurrilous, the representation of conventionality and irony, to chase after the bourgeois promise of a happy family, to expose it and at the same time apparently to confirm its questionability.

(Translation: Daniel Jones)